Finding Place, Shifting Perception: From Landscape as Image to Landscape as Cosmology

We cannot physically transform the world through landscape design in ten days, but we can change the way we see the world and make place by shifting perception.

We cannot physically transform the world through landscape design in ten days, but we can change the way we see the world and make place by shifting perception.

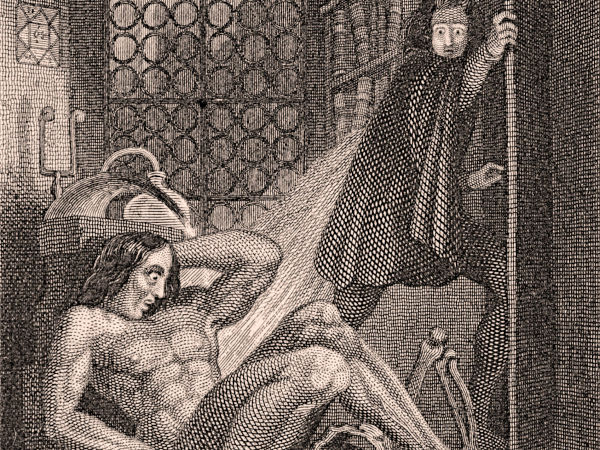

The Void can be found in the archetypal landscape between heaven and earth, humanity and divinity. It is a clearing for truth in Heidegger’s phenomenology.

In The Origin of the Work of Art, Heidegger uses the hermeneutic circle to show that working and thinking are processes of unconcealing existential truth.

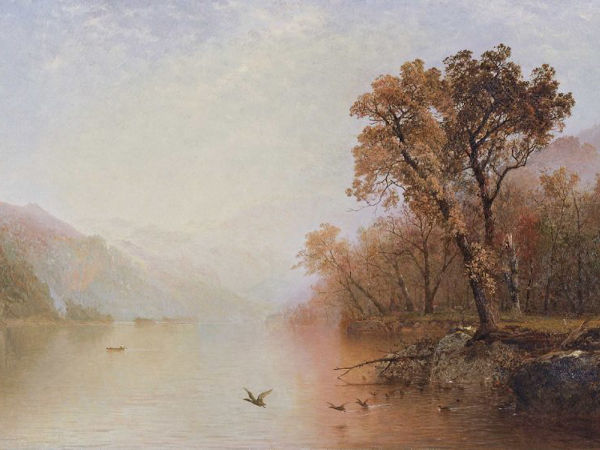

Johan Christian Dahl is the best representative of the three pillars of Romantic art: spiritual connection, scientific observation, and personal expression.

While Romantic science deliberated over nature’s purpose, the existence of souls, and Earth’s creation, Romantic art turned to these subjects for inspiration.

Romantic science was sentimental and subjective and was simultaneously inseparable from and at tensions with religious faith. Art revealed this duality.

This post discusses Burke and Kant’s sublime and shows examples of landscape paintings by Northern European Romantics, the Hudson River School and Luminists.

In Romantic landscape paintings we can find evidence of how science, faith, and the representation of nature shape the way we see landscapes and nature today.

Romanticism and nostalgia are paradoxes of modernity: to be authentic within illusions, yearn for individualism in connectedness, and find pleasure in mourning.