Finding Truth in the “Void” Through Chinese Landscape Painting

When I first went back to school to study the meaning of landscapes instead of designing landscapes, I was disappointed by what I discovered. I was told that landscapes were merely historical constructs created by social and cultural discourse, often as a result of biased agendas. So, I wondered, was there nothing more to landscapes than stories made up by “people of power”? Was I living a lie all along, believing that landscapes had some sort of magic to them?

Fortunately, I discovered the theories of material vitalism. These theories allowed me to suspend conventional logic to understand the power of things and other phenomena that cannot be easily explained. However, I was still dissatisfied. Fragments of materialism, despite their agency, could not explain the expansive poignant power I feel from landscapes. Ironically, when I stopped seeing landscapes as material, and instead, shifted my vision of landscapes as the invisible that all things came together.

An older version of this post was first published on an old blog from 2017. The content has been published in the article “The landscape of the Void: truth and magic in Chinese landscape painting” in the Journal of Visual Arts Practice.

The scene of the invisible

In Chinese, the word “landscape” can sometimes be called fēng jǐng 風景, literally translated as “wind scene”. This translation is paradoxical because this scene, this perceptual framework, contains the immaterial and invisible wind.

However, a Chinese landscape painting is traditionally called shān shuǐ huà 山水畫, literally translated as “mountain water picture”. The shift between landscape to landscape painting had somehow made the invisible scenery into something with material features such as mountains and water on paper.

The popularity of mountains and water features in Chinese landscape paintings are not mere coincidences. Buddhist and Daoist temples were often built high up in mountains so that philosophers could gain wisdom from their isolation and proximity to nature (Sullivan, 1979).

At the center is the Void

The Chinese phrase rén jiān xiān jìng 人間仙境, translated as “human between immortal border”, describes a stunningly beautiful landscape that exists between the realm of humanity and fairies. These landscapes are often scenes of mountains in the mists, alluding to a place reminiscent of both heaven and earth.

These fairy-like misty-mountain landscapes were the inspiration to my discovery that landscapes can be seen as the Void of our existential truth.

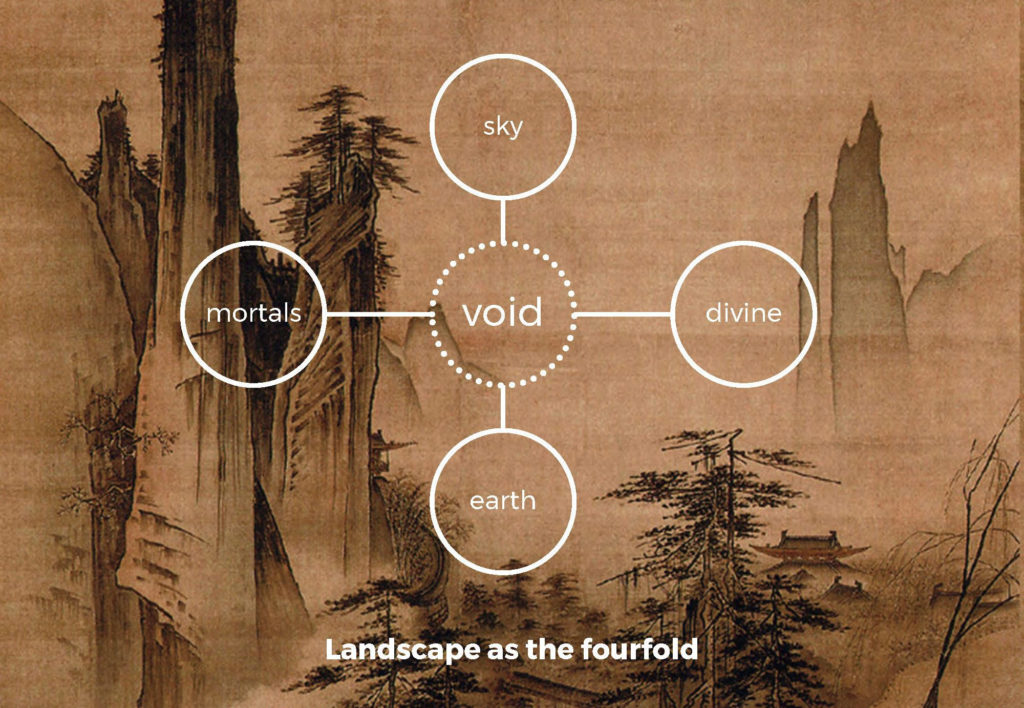

The Void is the source of all things in Daoism and can also be found at the center of Martin Heidegger’s (1971) fourfold cosmology of earth-sky-mortality-divinity. Since Heidegger was influenced by Daoism, the fourfold can easily be applied to philosophies relating to the Chinese landscape.

The parallel between Daoism, Heidegger’s cosmology, and landscape painting came to me one day when I found myself visualizing Heidegger’s fourfold over a landscape image in my mind. With the sky above, the ground below, and a spiritual connection within, a lightbulb moment came to me. I realised that the Void can be found in the Chinese landscape. This archetypal landscape exists in the realm between humanity and divinity, or literally in the Chinese phrase 人間仙境.

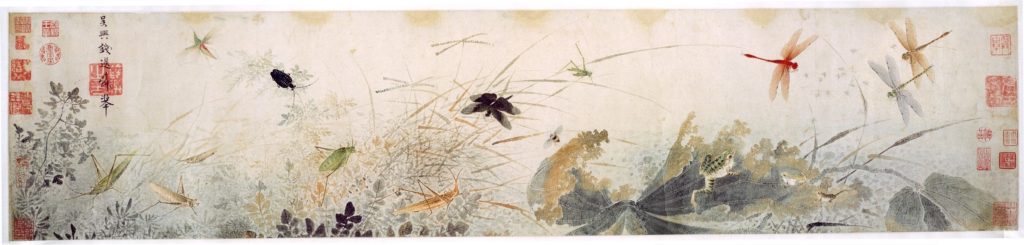

So if the Void is the clearing and the unconcealing of truth, according to Heidegger, then landscape as Void also embodies a form of truth. Therefore, Daoist philosophy is foundational to Chinese landscape painting. Unlike Western paintings that used perspectival techniques to capture a view from a single point in space and time, traditional Chinese landscape paintings attempt to transcend place and time by capturing the essences of elements from the experiences of nature (Sullivan, 1979).

Depth was created by layering elements, which is suggestive of Heidegger’s notion of Lichtung in which a clearing in a forest becomes an unveiling. Other paintings include bird’s eye views, which corresponds to the mountain vistas that philosophers found themselves in as they sought more expansive perspectives about the world.

Although there was a period in the Sung Dynasty (960-1279) when many Northern Chinese painters attempted to draw in perfect details and perspectives, the phase was short-lived and landscape paintings returned to Daoist principles of essences. (Sullivan, 1979).

Eastern vs. Western landscapes

Both Eastern and Western landscape painters were interested in “truth”. But although the Romantics yearned for existential authenticity, their fascination with human rationality (as influenced by Kant) and their need for individualism kept them trapped within a dichotomy of internal human subjectivity and external nature. Alternatively, the yin yang philosophy of Daoism acknowledges dualisms as complementary, and thus, metaphorically throws dichotomy into the Void.

One Romantic painter that can be discussed according to Eastern philosophy is J.M.W. Turner. My first impressions of Turner’s work was that he was well ahead of his times. Accordingly, Turner attracted polarized views from art critics. But most notably, he was adored by Victorian art critic John Ruskin.

From a Cartesian perspective, Ruskin’s love for Turner seemed strange because Ruskin claimed that art should be the expression of truth. Yet Turner’s work, especially in his later years, is so abstract that we can barely decipher this truth with our own eyes. However, from a Daoist perspective, Turner’s power to express truth in his artwork makes a lot of sense (Sullivan, 1979).

Turner’s truth was not the kind of truth that represents. Instead of replicating the physical aspects of nature, he was expressing an inquisitive truth towards nature’s principles.

People as landscapes

The human figure, usually found as peasants in Western landscapes, took place as pensive scholars in Chinese landscapes. Ironically, although almost inconspicuous in paintings, these figure still emit a kind of energy that illustrates a human-landscape relationship that is reciprocal. Japanese Meiji writer Masaoki Shiki’s phrase “people-as-landscapes” in the book Unforgettable People perfectly describes this relationship (Karatani 1993, 24).

Like landscapes, people also exist between the sky (heaven) and the land (earth). Between heaven and earth (tiān de jiān 天地間) is a place where things are both familiar and unfamiliar. The certainty and uncertainty of nature and life (i.e., mortality and divinity) crosses a physical landscape. From a Daoist existentialist perspective, this intersection is the Void. This landscape is practical and tangible and potentially magical or fairy-like, not because of its material nature, but because it was once impossible, incomprehensible, and invisible.

References:

- Heidegger, Martin. 1971. Poetry. Language, Thought. Trans. by Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Karatani, Kōjin. 1993. “The Discovery of Landscape,” in Origins of Modern Japanese Literature. Trans. and ed. by Brett de Bary. (London: Duke University Press.

- Sullivan, Michael. 1979. Symbols of Eternity: The Art of Landscape Painting in China. Stanford: Standford University Press.