Appreciation for Johan Christian Dahl

The Romantics looked to nature for divine revelation yet used objective observation of nature’s processes to yield truths into nature’s divinity. An individual’s creativity, which was seen as a gift from God, was considered a means to return nature materially back into the world of humans. Norwegian landscape painter Johan Christian Dahl, whose artwork merges mystic expressionism with scientific enthusiasm, is the best representative of the three elements of Romanticism: divine-spiritual connectivity, scientific accuracy, and personal expression. Here is a picture-focused appreciation post for this underrated Romantic artist.

An older version of this post was originally published in an old blog from 2017.

Background and spiritual philosophy

Despite Dahl’s relative obscurity in art history books, he was a prolific painter during his lifetime. He produced numerous landscape paintings of detailed studies and repeated scenes, so much that fellow artist and friend Carl Gustav Carus criticized him as over “materialistic” (Bang 1987, 16). But contrary to his abundant painting habits, Dahl came from a humble craftsman background which kept his art simple and unpretentious. Through his paintings, he revealed nature’s greatness as well as the nostalgia for his native Norwegian landscapes even though he spent most of his career in Germany.

Unlike his good friend Caspar David Friedrich, Dahl was not apparently concerned with the transcendental aspects of human-nature relationships. But in a down-to-earth way, Dahl related religious faith to nature. Dahl wrote that “the best writings and the most lucid religious ideas and feelings…[come] from statesmen, poets, speakers, and philosophers—and from those who study the natural sciences” (qtd. in Bang 1987, 247) because he believed that art and science, along with religion, aspired people to greater truth by “awakening [their] feeling[s] for nature” (246).

He stated:

…when Man transcends the raw state he feels and aspires to something nobler and more beautiful in life—and if he misses this too long, Man degenerates to refined animal gratification (and thus works against the development of the noble). Therefore the arts and sciences are not as unimportant as some people hold, but apart from religion these are of great importance for the human condition in a spiritual as well as economic sense. (Qtd. in Bang 1987, 246)

Style and popularity

Dahl’s pictorial conventions were very picturesque. Most of his landscapes follow a diagonal composition that was comprised of open vistas framed by mid-ground and foreground elements such as trees and cliffs that counterbalanced each other (Bang 1987). Although traditional pictorial conventions were important for Romantic artists, for Dahl, these conventions were practical rules for the perfect landscape image.

His earlier works reveal the influence of master artists: Claude Lorrain’s pastoral idealism; Danish painter Jens Juel’s lighting ambience; and Dutch painter Jacob van Ruisdael’s mountain and waterfall themes (Bang, 1987). However, Dahl developed his own painting style as he matured as an artist although his picturesque conventions remained consistent.

With the support of many patrons, Dahl was considered a popular artist during his lifetime. By successfully enhancing the image of his native Norwegian landscapes, Dahl is also celebrated as a significant cultural figure in his home country (Bang, 1987). However, in the grand narrative of European art, Dahl is often only mentioned in passing as Friedrich’s Norwegian friend and is less studied than other Romantic landscape painters such as Friedrich, Turner, and Constable.

Perhaps this is because Dahl’s style is considered less of a “breakthrough” than his contemporaries. Dahl does not represent the extremes of Romanticism, yet his paintings demonstrate the epitome of the Romantic landscape image. In this image is the search for truth in nature, and objective methodology in exploring this truth, and ways to express the subjective self. And so, there is much value in appreciating his artwork to understand the philosophy behind Romanticism.

Early works

Shipwrecks

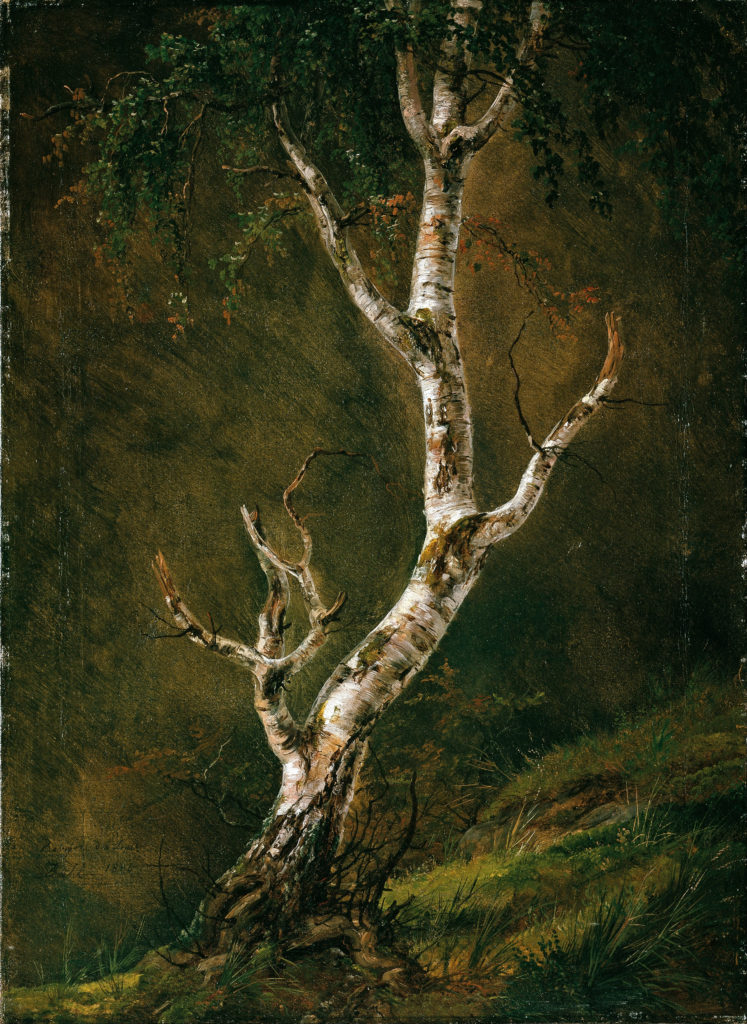

Tree studies

Winter and seasonal landscapes

Moon studies and moonlit landscapes

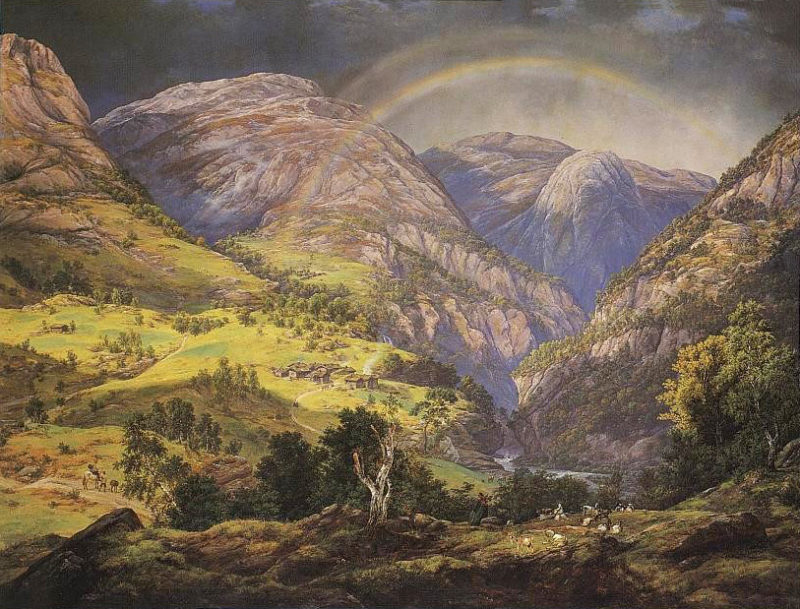

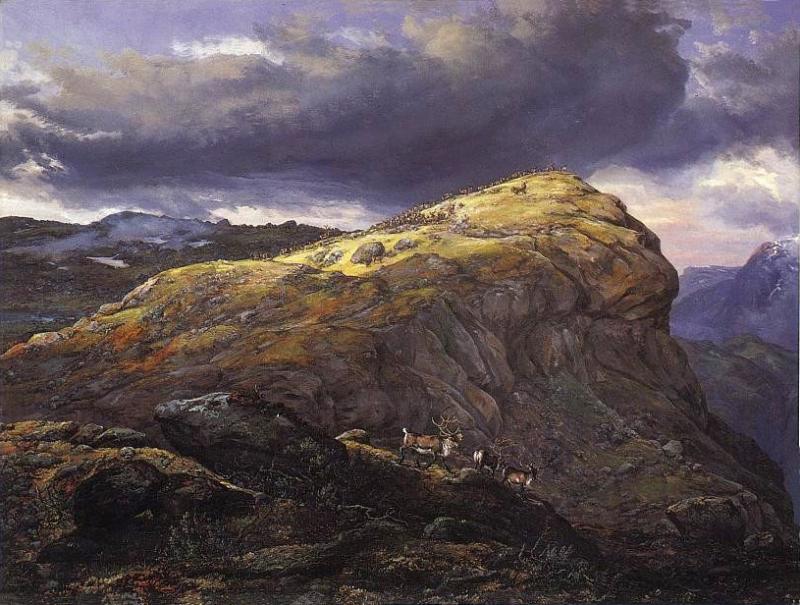

Later Norwegian landscapes

References:

Bang, Marie Lødrup. 1987. Johan Christian Dahl, 1788-1857: Life and Works. Oslo: Norwegian University Press.