Finding Place, Shifting Perception: From Landscape as Image to Landscape as Cosmology

While we cannot physically transform the world in 10 days, we can change the way we see the world in 10 days. Shifting the perception of landscapes is the first step to change the way we design landscape places.

This is a conference paper I presented at the 2017 World Design Summit Congress in Montreal, Canada. The theme of the congress was 10 days to change the world through design. An older version of this post was originally published on an old blog from 2017.

Landscape as mediator between nature and place

Martin Heidegger ([1927] 2010), one of the most important thinkers of the 20th century, described humanity’s existence (i.e. Dasein or Being) as the awareness of non-existence, non-identity, and non-belonging. In other words, we simultaneously have a desire for place and a fear of placelessness.

In cultures of profit, instant gratification and exploitation of resources, the distinction between place and placelessness is pushed to the sidelines. Simultaneously, in a globalized world, the discrepancies between cultures that value place and cultures that exist in placelessness are even more apparent.

Landscape is the mediator between nature and place. It tells the story of humanity’s relationship with the world. In Western history, landscape can be seen as a story of control: i.e. mind over external nature through painting, and power over material nature through landscape design. However, in the course of landscape history, there was a disruption in this control when landscape was subjective, passionate, and profound—in the Romantic era, landscape was enchanting.

Phenomenology and design

The Romantic landscape was a connection to divine nature, and a means to authenticity. Starting in the 20th century, the fascination of the enchanted landscape was mostly abandoned for an objectivity of nature and space. Edward Relph (1981) described it as landscape being “quietly slipped into a straitjacket” by objectivism, efficiency, and regulation (109).

Archaeologist Christopher Tilley (1994) suggested that most academics don’t understand landscapes because of the lack of experience in landscapes. Architect Botond Bognar (1985) claimed that architecture education and practice has been overly concerned with objective processes and rational solutions, neglecting human experiences. Furthermore, landscape architect James Corner (2002, 20), has argued that “contemporary theory and design have all but lost their metaphysical and mythopoetic dimensions, promoting a landscape architecture of primary prosaic and technical construction.”

While wonderful designs do exist, there has still been concern in the professions over the rationalization of design as logical manipulations of material and space, leading to a lack of sensitivity to place and experiential awareness. But awareness is constrained by a dominant way of seeing: in the modern worldview, awareness is one of binaries, particularly between subject and object. Consequently, phenomena that do not fit into the binary are invisible because we can’t comprehend their existence.

Phenomenology, in a way, is the study of the invisible: that is, the revealing of what was once concealed. I believe that landscapes are made of inexplicable qualities that can only be understood through shifts in perception. Although the enchanted landscape has mostly been lost in the conventional sense, there is still a lot of appeal for pragmatic landscapes in various disciplines, resulting in many different theories on landscape perception. However, these theories are mostly separated from each other and from real experience itself.

But these theories are not in conflict with each other. Rather they are different lenses that make landscapes more visible. Through a survey of scholarly texts about landscapes, I discovered 7 lenses to interpret landscapes. These lenses include landscape as:

- Power

- Image

- Patterns

- Sensory and emotional effects

- Dialogue

- Archetypes

- Cosmology or existential order.

I will be looking at two different lenses in this post: landscape as image and landscape as cosmology, which are two ends of the spectrum of representation.

Landscape as image

According to 18th century philosopher Immaneul Kant ([1790], 1952), a judgment of beauty on an object is both subjective and universal. That is, we believe that others should have the same judgment as we do. Landscape, through historical and cultural construct, has acquired a certain common impression of beauty. In fact, for aesthetics scholar T.J. Diffey (1993) the idea of landscape is already a prejudgment of beauty, which is learnt from the history of Western landscape painting.

Landscapes can make us feel awe, nostalgic, sentimental, or even close to the divine, but according to landscape architect Gina Crandell (1993), it was the pictorialization of nature that changed our opinion towards particular landscapes. We appreciate and even protect what we think as most beautiful as a result of its conformity with pictures.

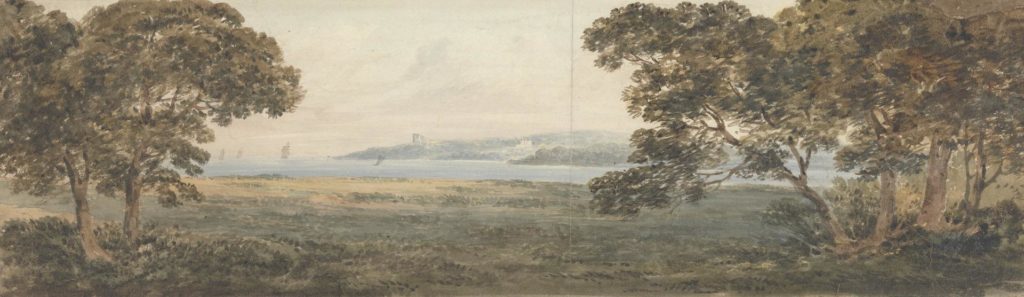

In my opinion, Romanticism was the most influential era of landscape perception. While we now like to put boundaries between art, religion, and science, the Romantic landscape represented a circumstance when these three areas were intricately woven together, prior to their separation in the 20th century. When we see landscapes today, we still see remnants of this tripartite relationship, however, sometimes in fragments such as through dreamy pastorals or objective scenic assessments.

The picturesque

The picturesque, a way to see nature as paintings, popularized by the writings of William Gilpin (1792) in the late 1700s, has stuck with us over the last couple centuries. Sir Uvedale Price, who introduced picturesque theories into gardening, influenced the way North America has designed our city parks: with winding paths, pastoral lawns, and groves of trees; nature separated from urbanity.

However, there is more to the picturesque. It is characterized by roughness, ruins, and mystery; in other words, it encouraged subjectivism and imagination. The picturesque taught the Romantics to frame their own subjective views of nature.

As a rejection to the over-rationality of 18th century Enlightenment, Romanticism was actually a modern movement to renew the wonders of human life. Nature’s purpose in relationship with the divine, and our purpose as humans in relation to nature was the force of discovery behind the movement. While Romantic science was a seeking of physical truth, Romantic art was the personal expression of truth.

Landscape as cosmology

Often these expressions of truth could not be represented merely by worldly forms, and instead took on what Hegel described as “ideal” forms ([1820], 2004). The sublime is a kind of ideal form. The sublime can be expressed, in one way, as the fear and repulsion of a dominating and divine nature, derived from Edmund Burke ([1757, 1998), or in another way, as the tension between pleasure and displeasure, when human rationality overcomes the unimaginable and physical powers of nature, derived from Immanuel Kant.

German artist Casper David Friedrich’s paintings are perfect examples of this tension. Human life is placed in contrast to a mysterious nature by lone figures in contemplation, pilgrimage, or ritual. While Friedrich’s work was not fully appreciated in his own time, there is now a renewed interest. Perhaps his portrayal of humanity’s vulnerable relationship with nature is what relates to the modern soul (van Os, 2008).

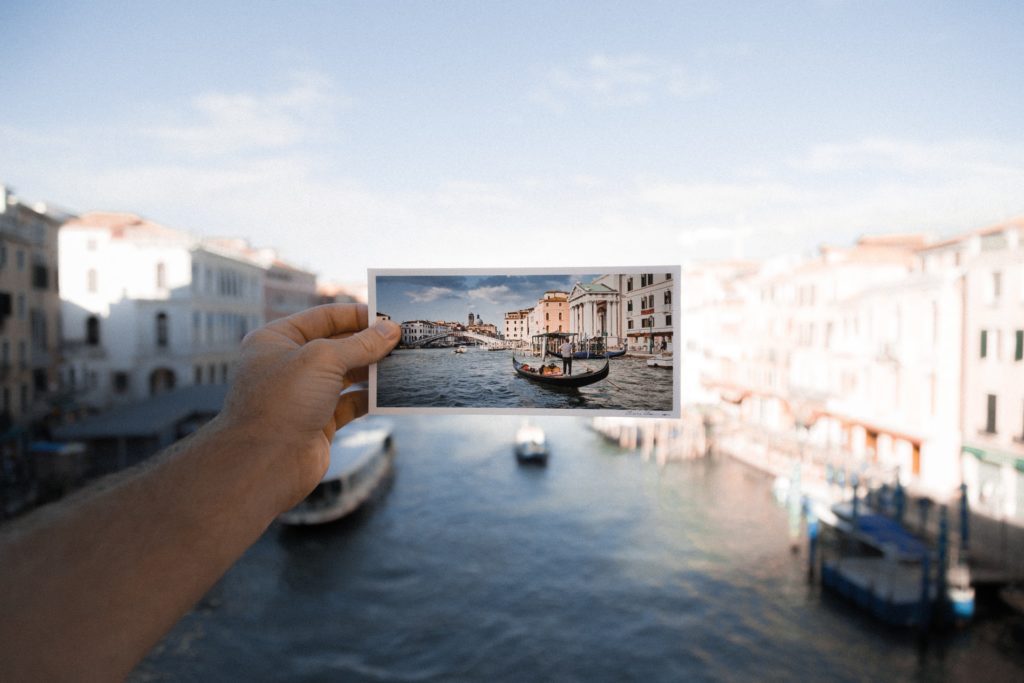

Today, from tourism to environmental activism, the media chooses a lot of what landscape images are considered beautiful. While perspective drawing turns 3D landscapes into 2D static images from a mind to hand process, photography eases this process of turning space into pictures even more. One step further, film allows the experience of space to be visualized as a series of image frames.

Truth in landscape

While we may think less of the landscape image today compared to the Romantics, there is both cultural and spiritual awareness hidden in landscapes. In landscapes is the search for truth and authenticity through nature (as seen from the Romantics) as well as the urge to control and objectify. This may be paradoxically but if we look at landscape in Chinese, literally called “scene of the wind,” we find the paradox apparent. The wind’s invisibility and non-representability is existent. In some ways, we can say that there is faith to this landscape.

Heidegger’s (1971) existential cosmology using the the fourfold of sky-earth, divinity-mortality suggests that landscape can be seen as a metaphorical and physical Void in Chinese Daoism. For a year into my studies, I couldn’t reconcile the mystery of landscapes using theories such as social constructivism or material vitalism, but an idea struck me when I imagined Heidegger’s fourfold over a Chinese landscape painting. Landscape, then, becomes the conjuncture of sky-earth-divinity-mortality. Landscape is the void, or in other words, the clearing for existential truth!

Two universal facts apply to all humans: 1) We dwell between the earth and the sky; and 2) We exist because we are mortal and are aware of death. Mortality is made more apparent through the realm of immortality, the realm of the divine, which plays out in similar yet diverse ways in the world’s religions. Humans cannot reach immortality, but we measure against it. Landscape helps us in this existential process.

Case studies: St. James Cemetery and Sugar Beach

In one of my PhD comprehensive projects, I analysed two landscapes using the seven ways of perception I listed above. One of the landscapes was St. James Cemetery, the oldest cemetery in Toronto. The other was Sugar Beach, a 21st century urban park in Toronto.

St. James Cemetery

St. James Cemetery is a place that sits between mortality and divinity, temporality and permanence. It is a place where the dead are sent off from the world of the living, and where the living question human limitedness and immortality through ritualization.

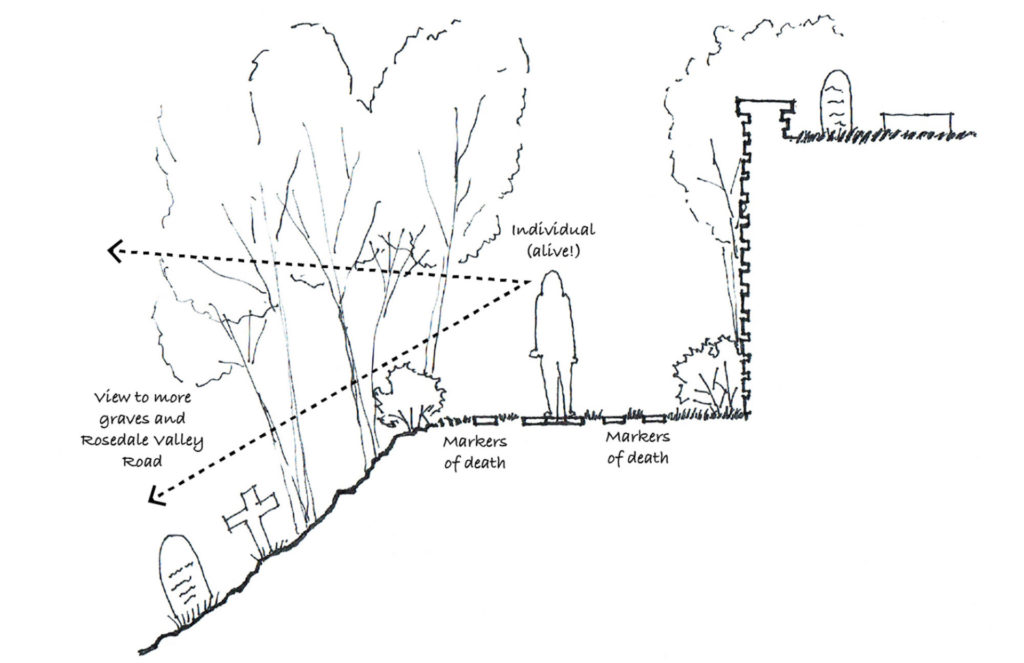

The highlight of my visit to St. James was when I was deliberately constricted at a narrow pathway adjacent to burial plaques next to a sloped terrain. The deceleration at the space encouraged more attentiveness and a feeling of slight uneasiness, especially when I reached what looked like a dead end into an unknown open landscape. The fear and repulsion, as well as the curiosity and fascination, was a reminder to Burke’s notion of the powerful sublime nature.

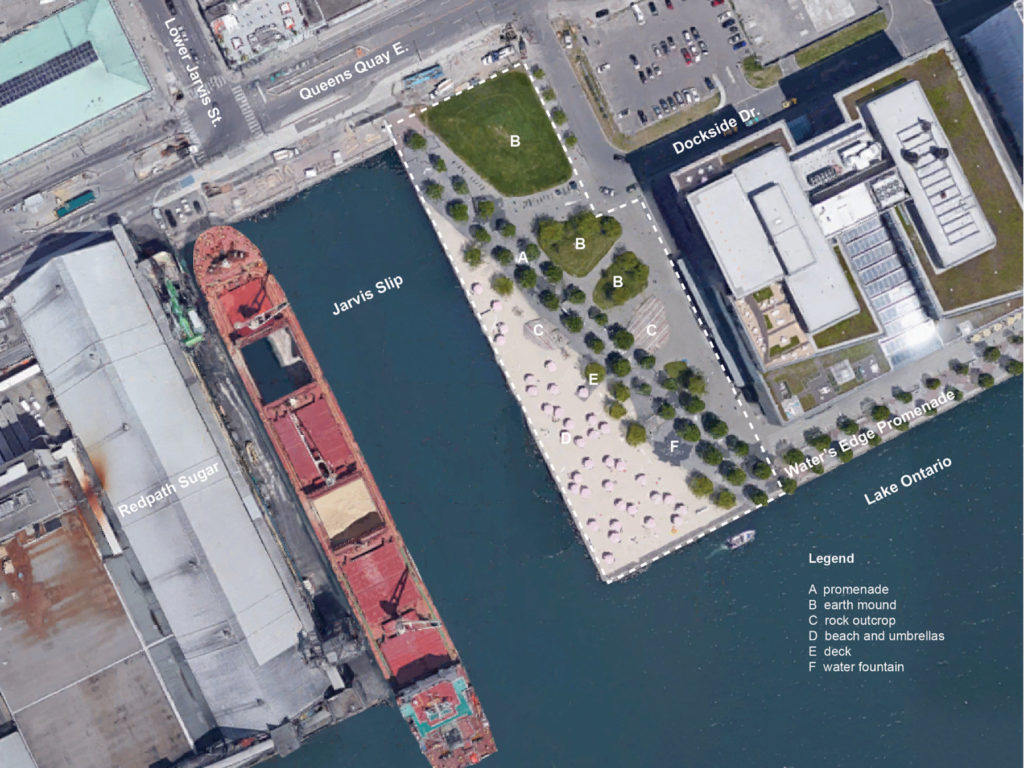

Sugar Beach

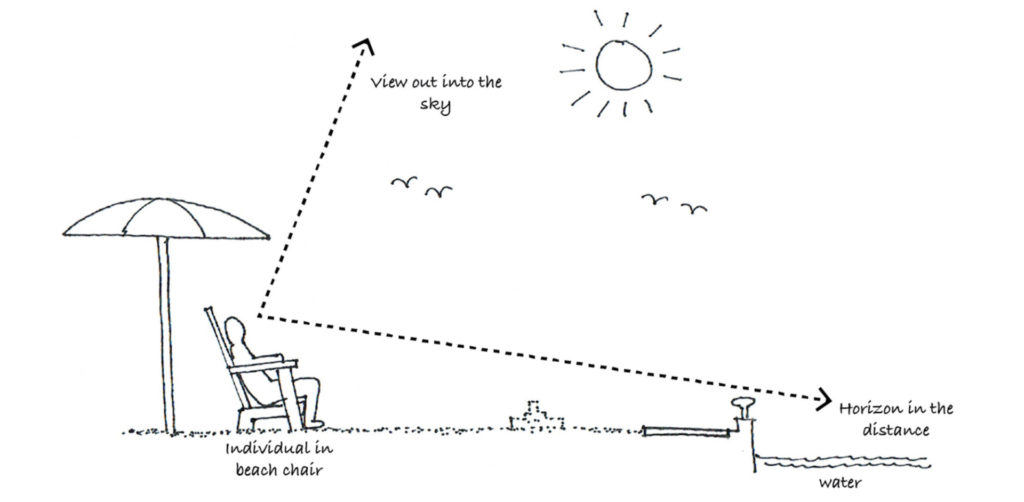

Sugar Beach, on the other hand does not look like a landscape that alludes to a cosmological order at first glance, but experientially, it is a very contemplative space. The most poignant moment that I remember from the park was simply the serenity of sitting in the beach chair. Once I was in the reclining seat, I did not want to put the effort in getting up. Consequently, I started staring out into the sky and the water.

The beach setting emphasizes the horizon where the sky meets the water. The paradox of the horizon is that it is unreachable: no matter how much we move forward, it only changes to reflect our efforts to get closer. This phenomenon describes humanity’s existence in the world, diminutive compared to the universe around us.

As I sat on the chair, I was receptive of the sensory conditions around me. Although I was surrounded by people, they did not disturb me, and I had the complete authority to decide when I wanted to leave. Although I was part of a bigger open space (to the extent of the elusive horizon), I was still protected in my own mental and physical space. Kant’s notion of the sublime caused by rationality over unpredictable nature comes to mind. Regardless of my existence in the greater world, a sense of control remained in me.

The body paradox

So, how does the Romantic landscape image and its twist into Heidegger’s existential fourfold relate to landscape design, especially from what I learned from these two case studies? From these two landscape studies, I learned that slowing down or stopping movement, has an effect to create a stronger attentiveness within me towards my environment. The highlighted moments in these two landscapes were created by feelings that developed out of the tension of paradoxical conditions.

At St. James Cemetery, the space was both compelling and repelling. My body was free and able to move while the surroundings felt tight and compressed around it. On the other hand, Sugar Beach provided a quiet contemplative space in a very open and public environment. My body was protected, but was simultaneously exposed to an expansive landscape. Both landscapes catered to the individual human body.

Cross sections of tight path at St. James Cemetery (left) and expansive seating at Sugar Beach (right).

Design for the soul

Based on my discovery of the body paradox, it would seem that if an established set of criteria including the traits of the end users were identified, landscape architects and designers could create memorable experiences by controlling space, particularly by slowing the body down. However, because every experience is unique, there are no guarantees that an intention in a design will always result in a particular experience.

Choreographed design involves a mechanized and rational process that does not speak to the poignancy of a place. And since experience is not mechanical, I believe that design should also not be mechanical. Although landscape images today are usually treated as merely 2D pictures, for the Romantics, the landscape image was a bridge between the divine and the human soul. This sacred view of landscapes can help us change the way we design.

For Kant ([1790], 1952), the genius is an artist who had the natural and divine talent to bring beauty into the world. In parallel, the poet, for Heidegger (1971), is someone who could unconceal the holiness that is lost in everydayness. The artist and the poet act as the middle person between the realms of heaven and earth. Through their creativity, the artist and the poet provide yardsticks for other fellow beings to measure against.

Specifically, this measuring is about human humility or faith in the unknown.

At St. James Cemetery and Sugar Beach, inspiration is provided at moments of opportunities, not as prescriptions. For instance, I did not purposely intend to think of life and death at the cemetery path, but in proximity to symbols of death (e.g., burial plaques and possible dead ends), I was encouraged to measure myself, as a human being, against death and the unknown. Neither was I thinking about earth and sky at Sugar Beach. But in the comfort of a beach chair, in front of an expansive view, I was invited to measure myself, as a human being, against the greater world.

Taking a leap of faith to see differently

Could we take a leap of faith and believe that poignant places are those that move the soul?

Or is imaginable that a part of one’s soul can be transferred between designer and landscape?

Or perhaps, a part of the designer’s soul can be passed into the landscape, and inadvertently, move the soul of a visitor?

I will never know for certain what the answer to these questions are, so I choose to believe that the answers to these questions is a big YES.

Sometimes, things are imperceptible not because they do not exist, but rather because of the way they are perceived. Ironically, to perceive clearly, we often need to start looking at things through different lenses. While there is no singular way to see landscapes, I am certain that meaningful and poignant landscapes require depth of perception.

The straitjacket that Edward Relph described can be removed, and the modern landscape can be re-enchanted, but only if we can see the straitjacket and imagine the enchantment. To me, a poignant landscape exists in the same vein as a poignant piece of artwork or poetry.

Therefore, landscape architects and designers have the opportunity to take on similar roles as Kant’s artists and Heidegger’s poets, that is, by creating moments of faith to humanity in landscapes that can touch the soul, evoke emotions, or simply inspire thoughts of a greater existence.

References:

- Bognar, Botond. “1985. A Phenomenological Approach to Architecture and Its Teaching in the Design Studio,” in Dwelling, Place, and Environment: Towards a Phenomenology of Person and World. Edited by David Seamon and Robert Mugerauer. Dordrecht, Netherlands: M. Nijhoff.

- Burke, Edmund. [1757] 1998. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, and Other Pre-Revolutionary Writings. Edited by David Womersley. London: Penguin Books.

- Corner, James. 2002. “Theory in Crisis,” in Theory in Landscape Architecture: A Reader. Edited by Simon Swaffield. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Diffey, T.J. 1993. “Natural Beauty without Metaphysics,” in Landscape, Natural Beauty and the Arts. Edited by Salim Kemal and Ivan Gaskell. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Crandell, Gina. 1993. Nature Pictorialized: “The View” in Landscape History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Gilpin, William. 1792. Three Essays: On Picturesque Beauty; On Picturesque Travel; and On Sketching Landscape: To Which Is Added a Poem, on Landscape Painting. London: printed for R. Blamire.

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. [c.1820] 2004. Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics. Edited by M. J. Inwood, trans. by Bernard Bosanquet. London: Penguin Books.

- Heidegger, Martin. [1927] 2010.Being and Time. Edited. by Dennis J. Schmidt. Trans. by Joan Stambaugh. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Heidegger, Martin. 1971. Poetry. Language, Thought. Trans. by Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Kant, Immanuel. [1790] 1952. The Critique of Judgement. Trans. by James Creed Meredith. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Price, Uvedale. An Essay on the Picturesque, as Compared with the Sublime and Beautiful; and on the Use of Studying Pictures, for the Purpose of Improving Real Landscape.

- Relph, Edward. 1981. Rational Landscapes and Humanistic Geography. London: Croom Helm.

- Tilley, Christopher. 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths, and Monuments. Oxford: Berg.

- van Os, Henk. 2008. “Casper David Friedrich and His Contemporaries,” in Caspar David Friedrich & the German Romantic Landscape. Aldershot, U.K: Lund Humphries, 2008.