Between Science and Mystery: Representing the Intangible in Romantic art

Science in the Romantic era was about searching for truth, uncovering the mysteries of life, and questioning morality, human authority, and faith. Nature was the source of this pursuit. While scientists deliberated over issues of the soul’s existence, nature’s teleology, and the creation of the earth, artists turned to these subject matters for inspiration. This post describes four areas of Romantic science (i.e., plant biology, geology, meteorology, and astronomy) that inspired artists to explore their artwork in new ways.

This is part 4 of a 4-part blog series that eventually got published as the article “The Romantic landscape: A Search for Material and Immaterial Truths through Scientific and Spiritual Representation of Nature” in the Athens Journal of Humanities and Art (2020). An older version of this post was originally published in an old blog from 2017.

1. Plant ontology: nature as God’s design

Romantic theories of archetypes and morphology were strong precursors to Darwin’s theory of evolution. One relevant theory was Schelling’s Romantische Naturphilosophie. In his theory, external nature was a product of the mind, but the mind was also a creation of nature. Therefore, according to Schelling, internal and external nature both originated from an “absolute ego” that existed prior to consciousness (Richards, 2002).

Schelling believed that this “absolute ego” originated from an archetype of a dynamic force which all organisms evolved from. (Side note: Doesn’t that sound like the Dao?) But for Goethe, this archetype was not determinate of an organism’s final stage of succession. New properties could appear, suggesting that new organisms could be created from old ones (Richards, 2002).

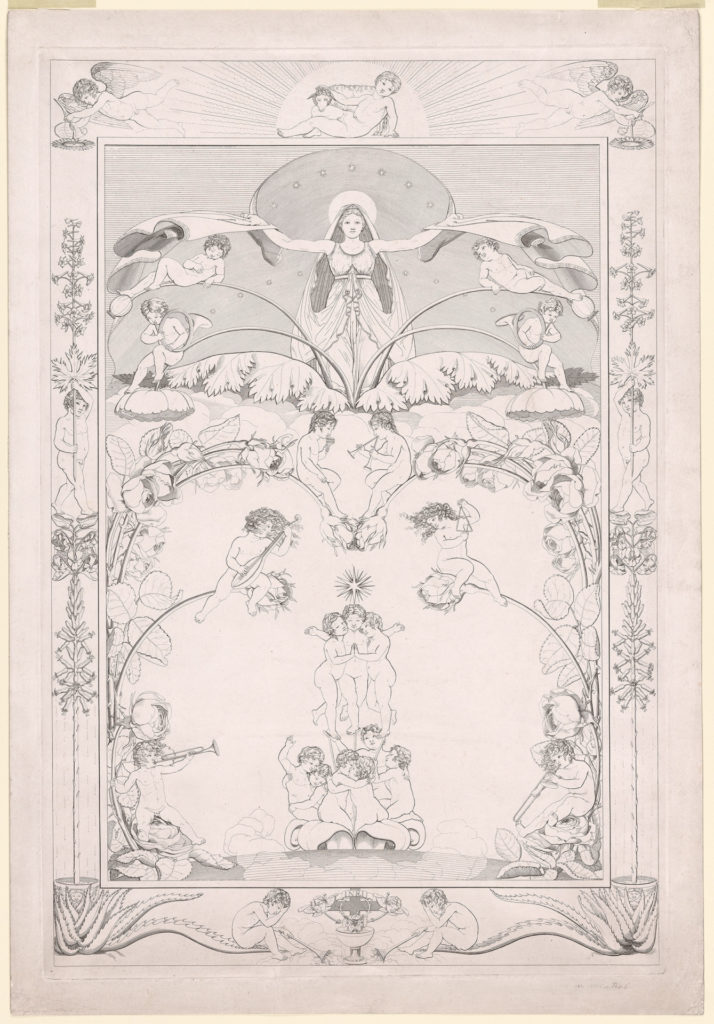

From a teleological perspective, Schelling and Goethe’s theories suggested that organisms could have unique self-motivated essences. In other words, the existence of a soul was a question that persisted among these Romantic thinkers. Similarly, for many Romantic artists, such as Philipp Otto Runge, the presence of an essence or a soul-like quality in plants was certain.

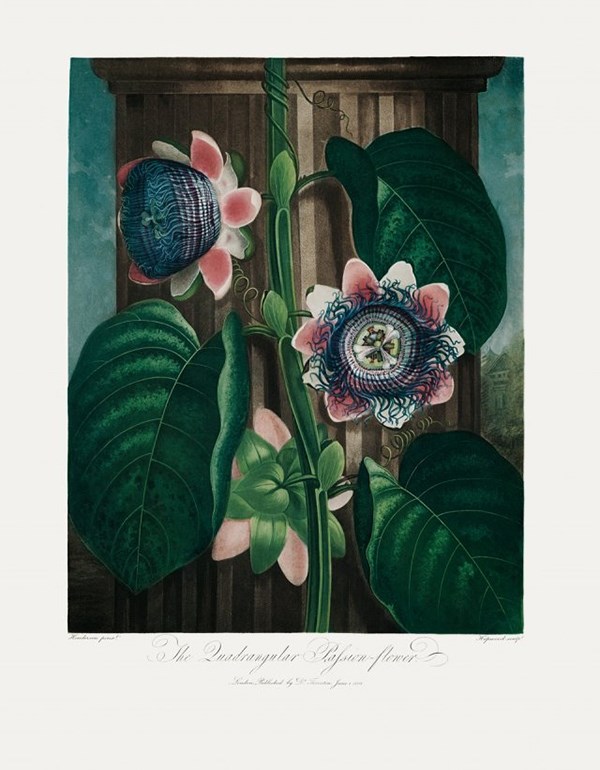

While Runge’s approach to botanical representation goes back to his mystical perspective on plant ontology, a direct link between science and botanical art can be found in the prints of Robert John Thornton’s The Temple of Flora (1798-1807). Perhaps because Thornton was an advocate for plant vitalism (i.e., the theory that an organism’s nervous system had electric properties), the flowers in his prints seem to have a surreal quality to them. Personified as specimen plants floating or growing in unrealistic conditions, these flowers and their landscape backgrounds are reminiscent of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century human portraits.

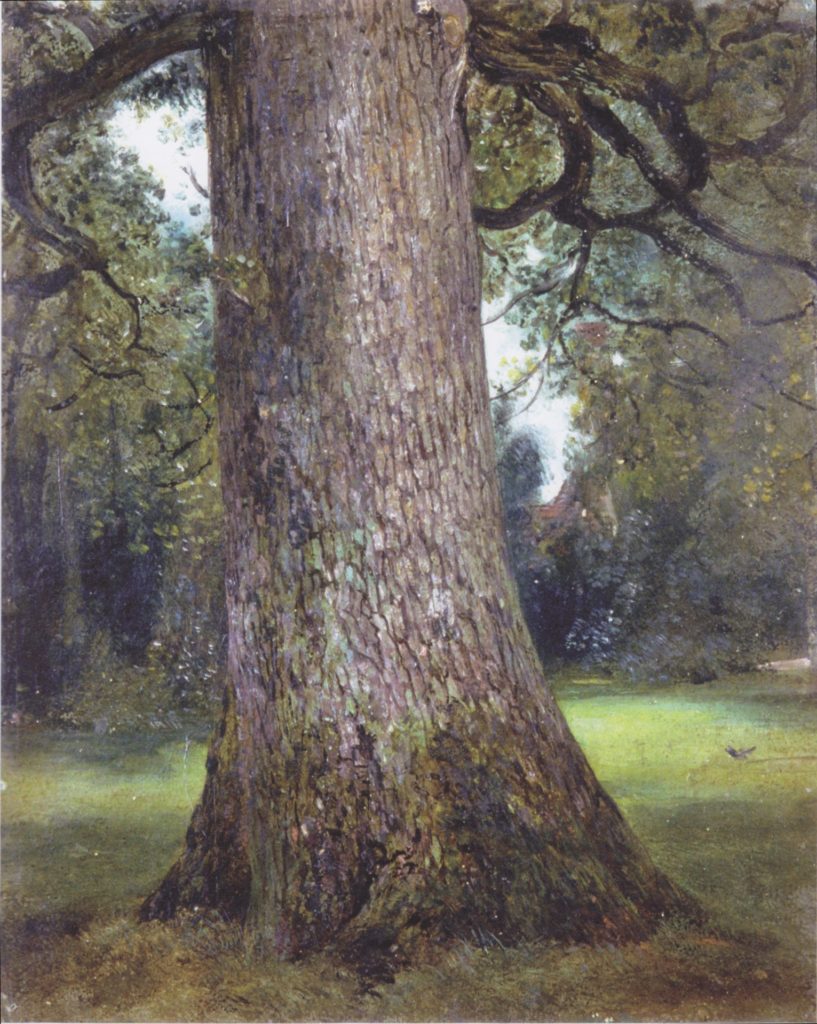

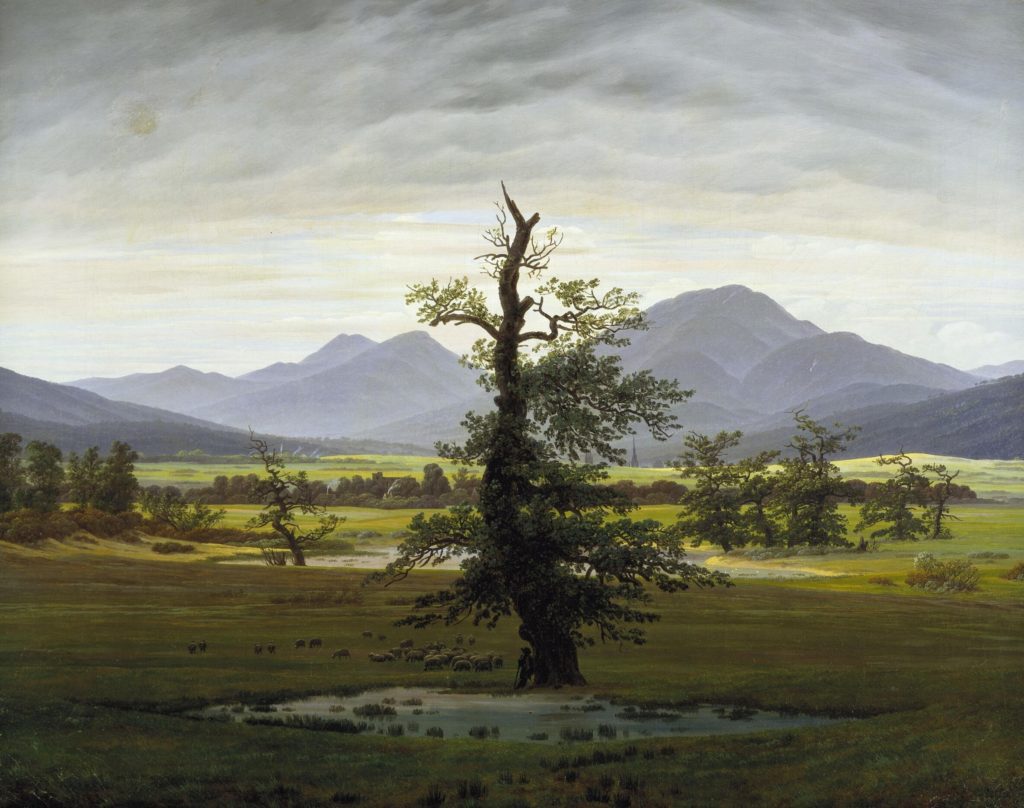

Among all plant material to be personified, the tree is perhaps the most symbolic of the connection between humanity and divinity. Therefore, lone trees were also commonly found in the works of major Romantic landscapists.

2. Geology: Alternative narratives of Earth’s creation

Prior to the 18th century, conventional belief had the Earth originating according to the Christian narrative of the Great Flood. But with the increased development of scientific and mining methods for geological studies, debate also increased over the Earth’s origins. Scientific expeditions such as the Grand Tour also gave people opportunity to see more natural wonders of the world.

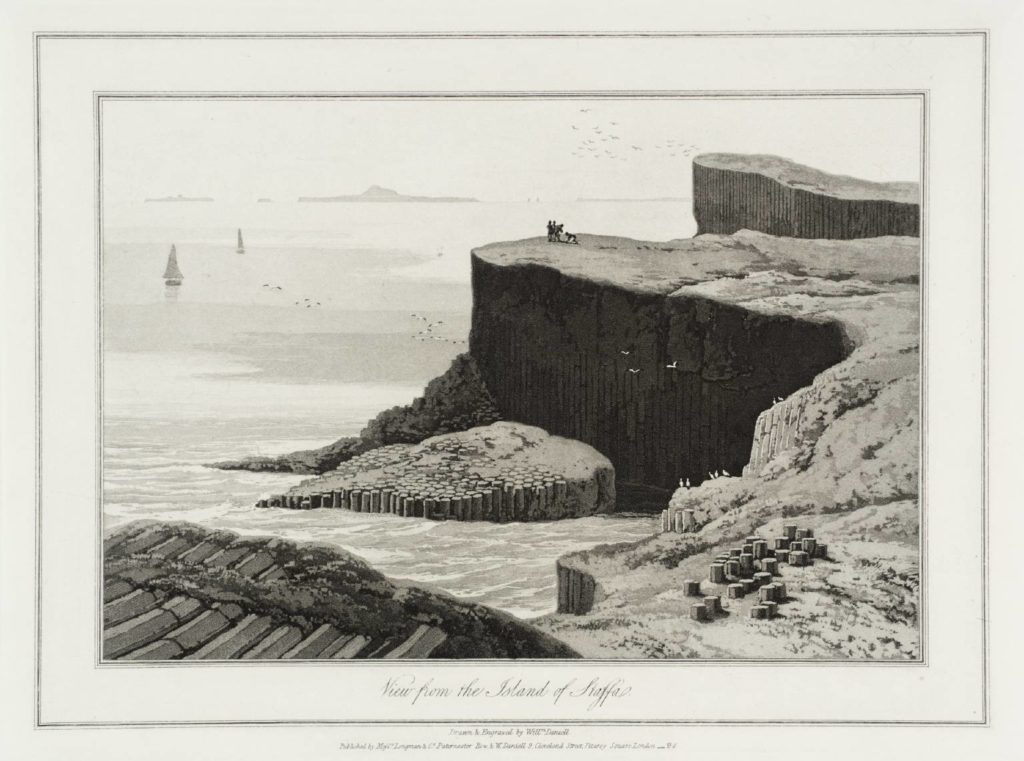

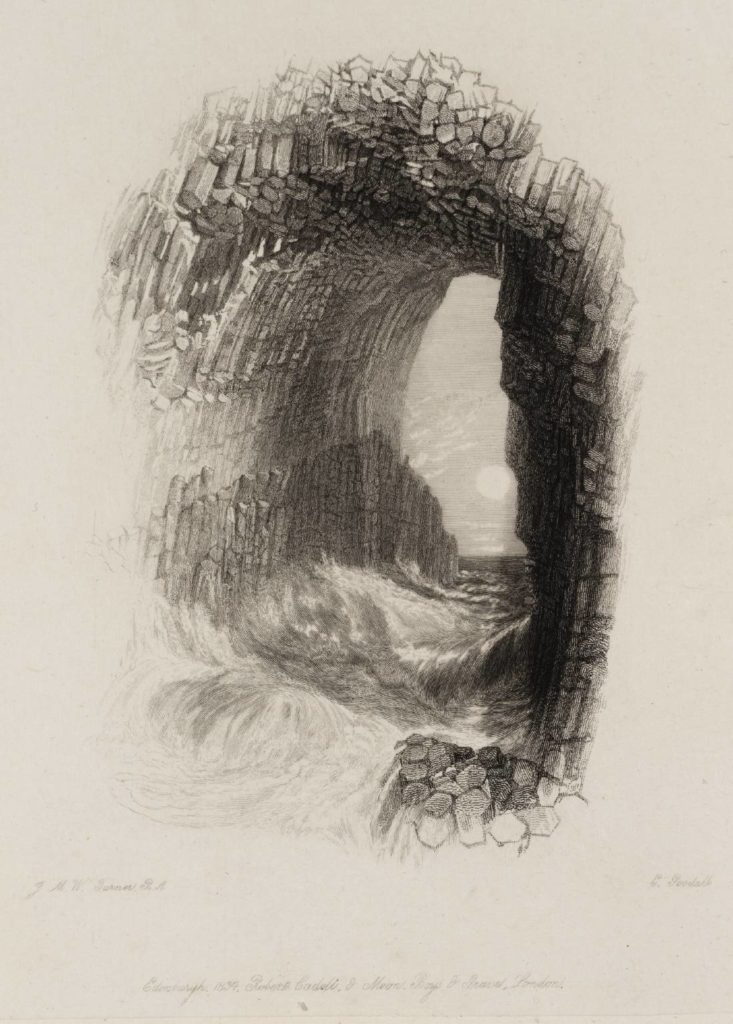

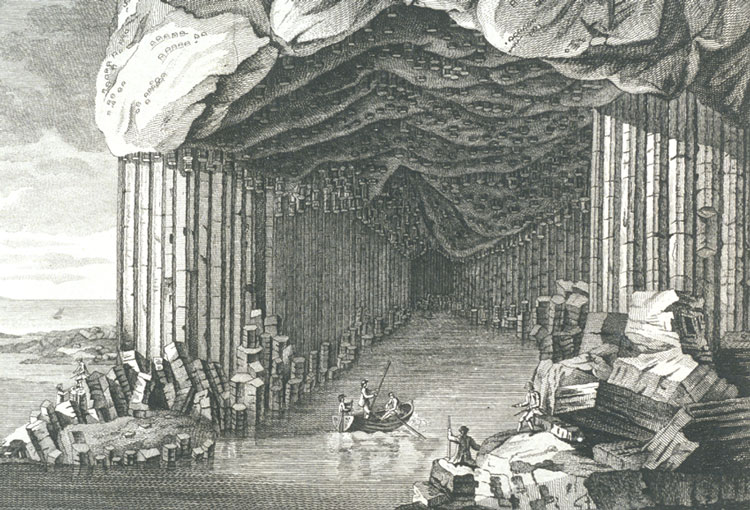

As these voyages were often accompanied by artists, these natural wonders were captured in paintings and illustrations. In these illustrations, we can see how explanations of the Earth’s origins shifted from religious to scientific. Fingal’s Cave, located in the Isle of Staffa west of Scotland, in particular, was a geological feature that showcased the evolution of representation and its relation to scientific knowledge.

The earliest prints of the structure show the cave as an architectural masterpiece, comparable to a natural cathedral. At this time, geologists were arguing over whether the structure was formed from “neptunist” or “vulcanist” process (i.e., rocks formed by mineralization in water versus rock formed by volcanic processes). But nevertheless, they still believed that the structure was a creation from God.

However, James Hutton, a supporter of the vulcanist theory, proposed a more controversial theory. Instead of a religious narrative, he suggested that the striatal layers of the rocks themselves held the answer to the Earth’s formation (Klonk 1992). This theory was sacrilegious for some, but for others, it merely mirrored early morphology theories in that God was the divine designer.

Regardless, the debate over the origin of the rocks generated more interest in Fingal’s Cave, leading to different perspectives and interpretations of the landscape structure. Some artists approached the structure objectively while others looked for picturesque or subjective qualities to represent. Fingal’s Cave was so inspirational for artists that it was even interpreted in a musical composition in Felix Mendelssohn’s (1809-1847) Hebrides Overture (also known as Fingal’s Cave).

3. Atmosphere: Nature’s process as objective and analytical phenomena

The Romantics were also interested in the ephemeral. Fog, mist, and changing cloud formations were common subjects in their paintings. The transience of the atmosphere combined with the rigour of scientific observation encouraged Romantic artists to observe and represent nature more systematically through approaches in naturalism.

For British Romantic landscape painter John Constable, clouds and rainbows were important nature studies. Although Constable produced numerous cloud studies, he was not interested in the taxonomy of cloud patterns. He was interested in the transience of the sky at specific moments in time, space, and weather conditions (Vaughan 1978).

Constable also studied rainbows, a traditional symbol of Christian faith, through studies of prisms and optics. Although objective in his approach, Constable still considered the concept of nature as a Godly creation. Painting nature accurately, for him, meant representing God’s creation truthfully (Wordsworth et.al. 1987). See Constable and other artists’ paintings of rainbows below.

4. Beyond Earth: A conquerable cosmos

In most cultures, the sky is considered the heavenly home of celestial figures and is integral to the stories of our cosmic origins. Between the darkness of the night sky and the twinkling of stars and planets, we encounter mystery and wonder. Unsurprisingly, the night sky is a sentimental part of Romantic art.

However, alternative narratives to the heavenly sky surfaced as new astronomic discoveries appeared prior to and during the Romantic period. For example, the laws of gravity and motion in the 1st scientific revolution set the foundation for a new scientific narrative. Next, the development of spectroscopy and astrophotography in the 2nd scientific revolution allowed the mysteries of the sky to be analyzed and represented.

Therefore, representations of the moon during the Romantic era ranged from sacred-symbolic to nostalgic-atmospheric to extreme realism. Eventually, with the expansion of scientific knowledge to outer space, the moon, which was once only attainable as a mytho-poetic element, became a domesticated matter within the body of human knowledge.

Despite science, landscapes cannot be conquered

The Romantic era, certainly, was an interesting time for humanity’s relationship with nature. The ambiguities between science, faith, and art made humanity’s pursuit of authenticity all the more enticing. Yet, I can’t help but wonder if somewhere in the obscurity, we made the wrong turn. Did humanity confuse the pursuit of self-discovery, as the Romantics had yearned for, for a conquest of nature’s knowledge to displace as our own? And has science conquered nature to a point that we have lost that chance to re-discover the truth about ourselves?

Nevertheless, I believe that science cannot conquer landscapes. Science can capture the materiality of nature and change its narrative (and consequently change our perception of it), but there is something within landscapes that will continue to humble humanity. That is because landscapes are more than material, and more than social narrative; landscapes embody a sacred truth about our inner worlds.

Therefore, the power of nature found in landscapes, either through a lived experience or through a piece of artwork, cannot be diminished by the human ego. And to me, that is why science came to exist in the first place—so that we can come closer to the mystery of our own existence. So let us use knowledge not to as a means to win over our world but to return ourselves back to the wonders of the world.

References:

- Klonk, Charlotte. 1996. Science and the Perception of Nature: British Landscape Art in the Late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Koerner, Joseph Leo. 2009. Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape. London: Reakton Books.

- Richards, Robert. 2002. The Romantic Conception of Life: Science and Philosophy in the Age of Goethe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Spencer-Longhurst, Paul. 2006. Moonrise over Europe: J.C. Dahl and Romantic Landscape. London: Philip Wilson.

- Vaughan, William. 1978. Romantic Art. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wordsworth, Jonathan, Michael Jaye, and Robert Woof. 1987. William Wordsworth and the Age of English Romanticism. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press